اضيف الخبر في يوم الإثنين ١٢ - سبتمبر - ٢٠١١ ١٢:٠٠ صباحاً.

9.11: Ten Years Later

by Stephen Schwartz

Folksmagazine [India]

September 11, 2011

http://www.islamicpluralism.org/1891/911-ten-years-later

.

It is challenging to write about the 10th anniversary of the Al-Qaida attacks on the U.S. in 2001.

Challenging, first, because recollections of the events are painful and distressing, even after a decade.

- The Comedy of the Ten Men Promised of Paradise

- The Ten Commandments in the Quran

- Fatwas Part One-Hundred-and-Ten

- Whom we grant him long life we reverse him in the creation, then they will not use intellect

- How I Lost My Parents Twenty-Five Years Ago because of Visitors of Muhammad's Mausoleum!

- The Prohibition of Marrying Female Children and Debunking the Myth of Muhammad's Marrying Aisha When she Was Nine Years Old

- Fatwas: Part Ten

- The real Jesus as described in the Quran

- The Two Futures of the Arab World

Second, because so much will be written and said about this occasion that one must fear repetition of idioms that, seeming hackneyed or banal, dishonor the victims and heroes of that day.

Third, because I comment as an American Sufi Muslim, with a personal history combining the ethnic streams of the heartland – Christian on my mother's side – and the Jewish identity of a father who bestowed on me the family name "Schwartz" but without the religious upbringing it implies to most Americans.

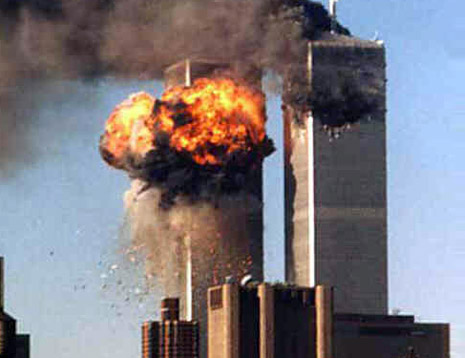

On the morning of September 11, 2001, I was at work at the Voice of America (VOA) in Washington, DC. I had the luck to be assigned as a national news editor. I heard the first mention that a commercial plane had hit the World Trade Center (WTC), turned to the TV monitors, and after a few minutes watched the second hijacked passenger jet strike the Twin Towers. The moment seemed unreal, like a scene from a film. Then came news of smoke visible from the direction of the Pentagon, across the Potomac, and rumors, including a false claim that a car bomb had exploded at the U.S. State Department.

VOA stood near the national Capitol building and many employees were distraught at the insecurity of the situation. The agency had never covered local events with the team-based method that daily newspapers and electronic news applied when reporting on earthquakes, major storms, and similar disasters. In addition, of course, 9.11 was a disaster unlike any other that had ever struck America.

The Al-Qaida assault was "post-modern." That is, it had a sped-up, instantaneous, totalistic character absent from past wars and attacks, such as the Japanese bombing of Pearl Harbor, with which it has been compared.

Journalism was already changing; traditional newspapers were giving way to the influence of internet commentary, and television news would soon acquire the characteristics of a polemical battlefield rather than a sedate discussion of world events. Developments came faster, with wider effects than before, but, with the exceptions of the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq, disappeared from public consciousness with greater rapidity than in the past.

When the Al-Qaida onslaught occurred, and it became obvious that radical Muslims were responsible for it, I could not help asking myself what my fate would be, as an American with Jewish associations, having affirmed the truths of the faith of Islam. I was proud to see how, during the first two years of the aftermath, Americans became united in purpose, to defend our homeland.

But the U.S. should have been better prepared for the horror, especially after the 1998 U.S. embassy bombings in East Africa and the 2000 attempt against the USS Cole in the port of Aden. I recall vividly the despair I felt at the sight of people employed in the WTC leaping from the higher floors, knowing they would die, but unwilling to burn to death in an inferno of jet fuel. Later I watched the video presentation in which the sound of their bodies bursting through the glass ceilings of the building's entryway was repeatedly heard. And I remember the uncertainty that seized Americans as lethal anthrax spores were sent through the mails. America's self-confidence, its global innocence, had been sorely tested.

When the jets seized by the terrorists slammed into the WTC, the Pentagon, and a field in Pennsylvania, Saudi Arabia, with a state ideology, Wahhabism, masked as its official religious interpretation, was still one of America's trusted allies, in a special category with Canada, the United Kingdom, Germany, Japan, and Israel.

Disclosure that 15 of the 19 terrorists active in the 9.11 raids were Saudi subjects changed the relationship between the U.S. and the Saudi kingdom, for some time, from a basis of trust to one of wariness. The U.S. has never acknowledged fully the role of the Saudi state, the Wahhabi clerical stratum, and their international networks in 9.11, and Saudi Arabia has, after a decade, failed to undertake a candid, public examination of its responsibility in an event that, in many respects, destabilized the whole world.

Among Muslims, aggressive manoeuvres by Saudi-backed Wahhabis had been a topic of comment for years, especially involving the Balkans, the Caucasus and, contrary to the current beliefs of many Westerners, Iraqi Kurdistan, where the regime of the late Saddam Hussein encouraged the penetration of Wahhabi agitators. I lived much of the two years leading up to 9.11 in Bosnia-Hercegovina and Kosovo. In both, the sense of Wahhabism as a phenomenon with a dangerous and expanding influence, financed from the Gulf states, was widely shared. But responsible U.S. representatives, unofficial as well as official, dismissed talk of the Wahhabi threat as intra-Muslim intrigue beneath notice.

Of the Muslim lands that have officially or semi-officially supported radicalism, the Saudi kingdom was, necessarily, most affected by 9.11. Saudi King Fahd Bin Abd Al-Aziz had been medically incapable of fulfilling his monarchical duties for years before the atrocities erupted in New York and Washington, followed by the sacrifice of passengers in a commandeered jet over Pennsylvania. Then-Crown Prince Abdullah, his half-brother, was designated as an unofficial ruler, but real power rested in the hands of Fahd's full brothers, Nayef and Sultan, and their four companions in the group known as the Sudairi Seven. Including Princes Abdul Rahman, Turki, Salman, and Ahmed, they were all sons of Hussah bint Ahmad Sudair, a wife of the founder of the contemporary state, King Abd Al-Aziz Ibn Saud. Sultan, the former defense minister and currently Crown Prince, and his son Prince Bandar, the former Saudi ambassador to the U.S., were the Saudis best known to Americans. Bandar had become a prominent figure in Washington society, flaunting his privileged access to the White House.

The U.S.-Saudi relationship, it was believed, and the possible alignment of Saudi Arabia toward a moderate position regarding Israel, were thought to have been reinforced after the Gulf War of 1991, when Kuwait – and by extension, Saudi Arabia – were saved from Saddam Hussein by U.S. intervention. Before then, U.S.-Saudi cooperation, through Pakistan, in driving the Russians out of Afghanistan, was also seen as an incentive for a close alliance. Criticism of the Saudi role in 9.11 was at first dismissed by some as "conspiracy theory."

Saudi ruling circles clearly were shocked at the international repulsion against them produced by the Al-Qaida offensive. In 2005, King Fahd died and was succeeded by Abdullah Bin Abd Al-Aziz, the current king. Abdullah had always been reputed to oppose Wahhabi domination over Saudi society, and once he assumed the throne, Abdullah indeed commenced a cautious but real reform program. According to sources close to the court, although most of the rest of the royal family appears committed to a retrograde style of governance, and the Wahhabi clerics stand as a major component of the social order, King Abdullah is proud of the small changes he has brought about. These include expansion of press freedom, lessening of discriminatory measures against the country's large Shia minority, which is concentrated in the oil-rich Eastern Province, small concessions toward the equality of women with men, creation of an educational establishment independent of the religious authorities, dismissal of hard-line Wahhabis from the judicial system, reduction of financial support to the hated "mutawiyin" or morals militia, and gestures toward interfaith dialogue with Jews, Christians, Buddhists, Hindus, and other faiths. The Saudi kingdom also sought to free itself of the burden of Al-Qaida by "exporting" terrorist cadres to Yemen, where they have gained influence and control over significant territories as "Al-Qaida in the Arabian Peninsula."

The theatre of global military response to 9.11 never encompassed Saudi Arabia itself, although the U.S.-led intervention in neighboring Iraq called forth an invasion across the Saudi-Iraqi border by Wahhabi "mujahideen" who wrought terror against Shia and non-Wahhabi Sunni Muslims, including the many Iraqi spiritual adherents of Sufism. Wahhabi extremism alienated the Iraqis, even those Sunnis opposed to the American-led military presence, and Al-Qaida lost the battle in that country – notwithstanding the persistence of terrorism there now. The main focus of conflict moved to Afghanistan, where the early victory of NATO forces against the Taliban regime was undermined by revival of the Taliban, with support from inside Pakistan.

Although, like Saudi Arabia, it seems often to have faded from attention in global media, Pakistan became, and is still, the most dangerous source of global terrorism. Jihadist forces in the ranks of its military and intelligence apparatus, incited by the extremist clerics of the Deobandi and Mawdudist schools, commit massacres in Afghanistan and India on its western and eastern borders, recruit terrorist foot-soldiers from its other neighbors among the ex-Soviet Muslim states such as Uzbekistan, send radical agents to Bangladesh and Myanmar, and subsidize zealots among the Muslims of South Asian origin living in the UK, elsewhere in Europe, and the U.S.

But Europe had already become exhausted with the Iraq war, and the world refused – and still declines – to look squarely at the Pakistan problem, as its further degeneration toward failure as a state seems inevitable. Even after the death of Osama Bin Laden while enjoying Pakistani military hospitality, adherents of the Pakistan-based terror apparatus, with its many components, shed blood across South Asia and plot new outrages in the West.

The acceleration of events after 9.11 left other questions unanswered and important issues insufficiently debated. One of these was the concept of "Islamofascism;" that is, of a totalitarian power ideology that, using religious fundamentalism as a pretext, shared the violent characteristics of fascism and Stalinist communism before it. "Islamofascism" should have been debated anew with the commencement of the recent series of revolutionary changes in the Muslim countries. These began with the stalemated opposition to electoral malfeasance by the regime of Mahmoud Ahmadinejad in Iran in 2009-10, and then snapped, unexpectedly, the weak links of the chain of the world order in the Arab countries of Tunisia, Egypt, Libya, Bahrain, Yemen, and Syria. The ferocious Jew-baiting of the Ahmadinejad clique, the Libyan dictatorship of Mu'ammar Al-Qadhdhafi, with its pretensions to global Islamic proselytism, and the "secular" Arab nationalism of Bashar Al-Assad in Damascus all have shown striking resemblances to the classic fascism of Mussolini and Hitler. The "Arab Spring" (or, better, the Muslim Spring, considering the important of non-Arab Iran), which flourished in 2011, vindicated, for some commentators, the "Freedom Agenda" motivating George W. Bush's decision to overturn Saddam Hussein. Yet "Islamofascism" is forgotten – even as, I believe, it has enduring relevance in understanding the variants in the social order against which oppressed people, mainly young, in the Arab countries are fighting.

Another concept popular in the aftermath of 9.11 but, finally, neglected in public discourse is that of "a struggle for the soul of Islam." Such a conflict is, indeed, the foundation of Wahhabi radicalism, whether seen in Egypt where it has reemerged, in Yemen, or in the form of its Deobandi-Mawdudist homologue in South Asia. But if the pattern of this confrontation is clear to many educated and conscientious Muslims – especially in the competition of "modern" Islamist radicalism with traditional and Sufi modes of worship – it continues to elude the rest of the world's observers. In this context, the aggression of 9.11 may be viewed as aimed primarily at Muslims, to convince them that resistance to Wahhabi doctrines and their variants, including the Taliban and their Pakistani patrons, would have devastatingly destructive results for the Muslim umma. And so it has come to pass: Muslims make up the overwhelming majority of terror victims. Recognition of this dreadful reality may be a crucial aspect, along with the dissolution of the clerical state in Iran and of the Wahhabi monopoly on religious life in Saudi Arabia, in closing the cycle of Islamist radicalization – but the end of the arc of extremism, like all other historical phenomena, must be considered unavoidable.

The 10th anniversary of 9.11 comes when the world is distracted by the menace of economic collapse in the West and the spectre of Chinese expansion throughout the world – developments that may be linked to 9.11 and its aftermath mainly in psychological terms. We have yet to see how much the anguish and fatigue sown among Western leaders by the consequences of 9.11 will obstruct economic and social recovery, as well as a rational policy toward China. But to the ordinary observer, neither situation is promising.

For Muslim believers, in the Muslim-majority countries and in the West and the developed and emerging societies of Asia, the defeat of the fanatical impulse that revealed itself to the world on 9.11 is still the task with the highest priority. Muslims living in non-Muslim countries must demonstrate our sincere belief that the security for practice of our religion afforded us in the Western democracies and developed Asian countries merits our full participation in the defense of the institutions of popular sovereignty and pluralism. This has been the guidance of our faith since the time of Prophet Muhammad: that as Muslims living in non-Muslim societies, we obey the laws and customs of the lands to which we have emigrated, or, as in cases like mine, where we were born. There can be no deviation from this principle, if moderate, traditional Islam is not to perish in the crossfire between Islamofascists and Islamophobes.

Finally, Sufi Muslims throughout the world should view the 10th anniversary of 9.11 as an important occasion to reaffirm our essential message of love for the divine, love for our neighbor, respect for all religions, and meditation on the poison of theological bigotry in its effects on fellow-Muslims and non-Muslims alike. For the victims of the "9.11 decade" let us all turn to the mercy and compassion afforded us by almighty God.

دعوة للتبرع

الزواج من البوذية : انا منذ اكثر من سنتين تقريب ا ابحث عن اي دليل...

سؤالان: السؤا ل الأول : أنا طبيب إمتيا ز ، واعتب ر ...

إهدأ يا ابنى العزيز: ---------- ---------- ---------- ---------- ---------- السل ام ...

ابليس والملائكة: يقول الله عز وجل فى اقرآن الكري م (وإذ قال...

هارون وزيرا : ما معنى أن يكون هارون وزيرا لأخيه موسى ؟ وهل...

more